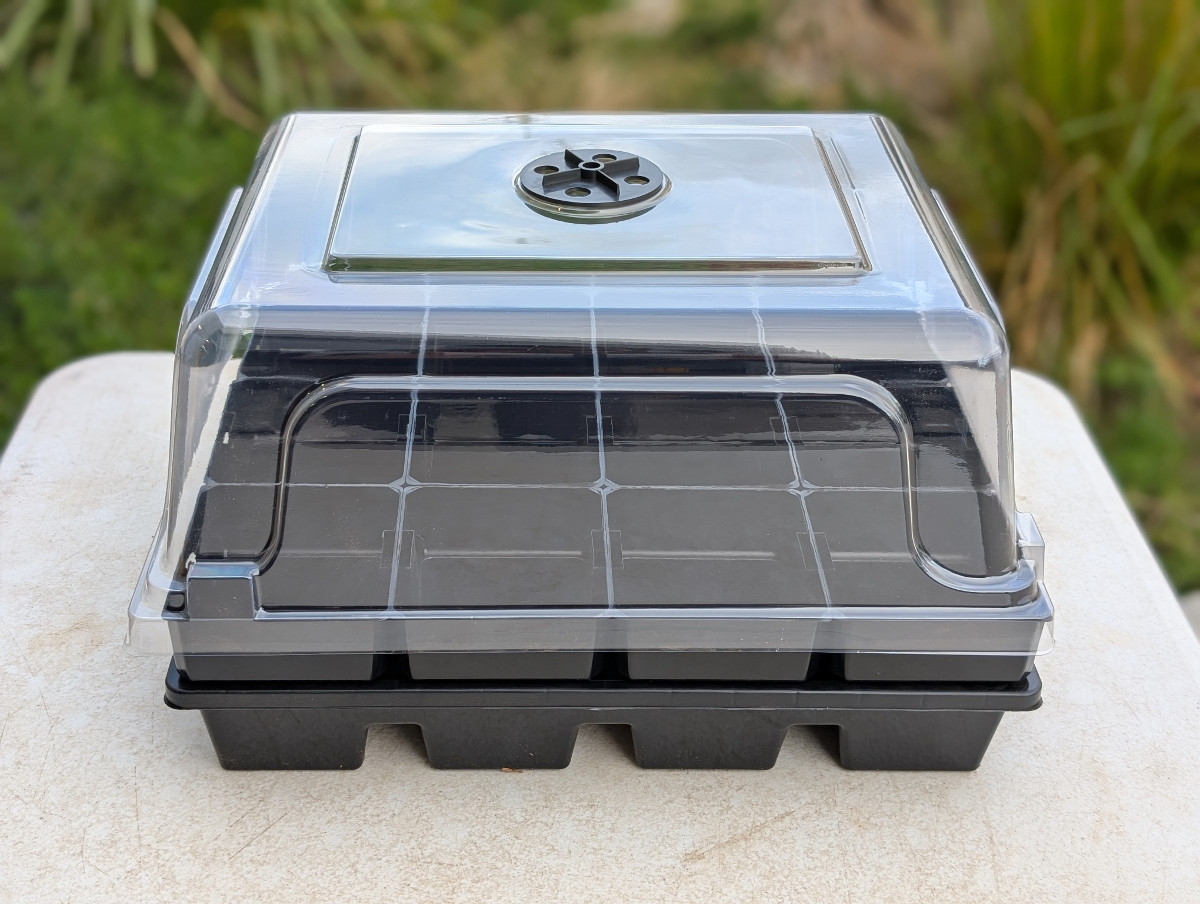

Our Greenhouse Lid is designed for maximum compatibility with a wide range of common Australian trays and pots. Take a look at the compatible products below to see how you can create your own mini-greenhouse!

Trays

The trays listed below are compatiable with our Greenhouse Lid:

***

Product: Drip Tray Solid Bottom

Product code: TRHG

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 1

.jpg)

.jpg)

Product: 10 Cavity Punnet Tray

Product code: TRS10X00

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 1

Product: Seedling Tray- Ridged Bottom

Product code: TRS349X

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 1

Product: 12 Cavity Punnet Tray

Product code: TRS12X00

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 1

Product: 30 Cell Propagation Tray

Product code: K30R

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 1

(product is pictured below in combination with a drip tray which is the standard combination)

Product: Half Tray Super Punnet

Product code: PUNSP00

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 1

(product is pictured below in combination with a drip tray which is the standard combination)

Containers

The containers listed below are compatiable with our Greenhouse Lid:

***

Product: Water Saver Punnet

Product code: PUNMWSS

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 10

(product is pictured below in combination with a drip tray which is the standard combination)

.jpg)

Product: Squat Punnet Pot- Small

Product code: PP100SQ00

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 12

(product is pictured below in combination with a drip tray which is the standard combination)

Product: Squat Punnet Pot- Large

Product code: PP116SX00

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 9

(product is pictured below in combination with a drip tray which is the standard combination)

Product: 10 Cell Punnet

Product code: PUN10PACK

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 2

(product is pictured below in combination with a drip tray which is the standard combination)

Product: 4 Cell Punnet

Product code: PP116SX00

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 4

(product is pictured below in combination with a drip tray which is the standard combination)

Product: 6 Cell Punnet

Product code: PUN6PACK00

Quantity to fit Greenhouse lid: 4

(product is pictured below in combination with a drip tray which is the standard combination)

Congratulations to our winner, Mcora Farming from Victoria! We loved the layout of your garden and were particularly charmed by you tractor and rusty beds!

Mcora Farming (VIC)

This months winner!

.jpg)

Mcora Farming said: We live with 6 people and needing more food options, 7 large custom steel beds 8mts long x 1 mtr wide, 1 bed on the ground for garlic/corn and then to top it off with an old rustic tractor with a seeder drill on the back, converted with herbs at the back of it. The veggie garden is surrounded by 40 fruit trees.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Mcora Farming said: An old tractor with the seeder has herbs growing all year round! Great feature to the garden

.jpg)

Mcora Farming said: These sunflowers were just amazing so tall and beautiful

.jpg)

Lucinda (NSW)

.jpg)

Mcora Farming said: Hi. My garden is my own quirky style. I have my zygocactus growing in my covered area & with a raised bed which at the moment I have full of silverbeet (which I love to eat ). It originally was for strawberries the raised bed. But at the moment it’s the silverbeet patch instead.

.jpg)

Mcora Farming said: Love this small area. I put some pots in to cheer up an otherwise boring small area. I’ve a nsw Christmas bush. A woolly bush. An azalea & a pot of polyanthus with some tête-à-tête daffodil bulbs ready for the warmer months & just few other flowery ones as well.

.jpg)

Mcora Farming said: I had this corner in my garden that was just asking for a feature. So I decided on to put beside my residing Venus statue a water feature. It’s a plastic half barrel pot with a solar powered water fountain floating in it. The birds love it & it brings more joy to my garden.

.jpg)

Jenni (QLD)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Jenni said: Wet soggy winter in the tropics. I like it, l add to the garden, my lemongrass, pawpaws, Thai basil, frangipanis with the beautiful hippie's but don't forget the dwarf beans. Adding colour with homemade structures.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Jenni said: Revamping the hanging baskets.

.jpg)

Jenni said: Adding colour to my garden.

.jpg)

Margi (NSW)

.jpg)

Margi said:

My winter vegetable patch is looking healthy with caulifower and broccolli that I grew from The Seed Collection seeds. I can protect the plants from the white moth as soon as it appears (often with the August westerlies) by zipping up the netted tunnels.

In my cool greenhouse (high tunnel shape) I am getting ready to dig in the next two gardens now full of an autumn/winter green manure crop. I will soon chop it into the garden beds and mix with mushroom compost, then leave it to mulch over winter ready for summer crops (mainly lettuce, tomatoes, capsicum and eggplants as well as cucumber).

.jpg)

Jo (QLD)

.jpg)

Jo said: Winter in North Queensland. Lots of corn.

.jpg)

Jo said: Zuchinnis, Beets, Tomato & Silverbeet

.jpg)

Jo said: Garlic in November.

Lucilla (TAS)

.jpg)

Lucilla said: Turning leaves into confetti in my winter garden. Nothing like a crisp morning and a bit of leaf-mowing fun!

.jpg)

Lucilla said: A little bee, a big reminder that even in my winter garden, life is still buzzing.

.jpg)

Lucilla said: Green and gold leaves and quiet paths — my winter garden is a gentle reminder that change can be beautiful.

Mr Aussie Dad (NSW)

.jpg)

Mr Aussie Dad said: My winter garden with summer veggies! With supermarket veggie prices sky high, I've turned our spare shower into a summer garden using cheap reflective solar blankets, a 150w LED grow light and 80w greenhouse heater. I call this my "Shower Farm".

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Mr Aussie Dad said: Suyo Long cucumbers and Calmart and Moscovich tomatoes in 20L buckets are growing like crazy. Yum!

.jpg)

Mr Aussie Dad said: An old, well-worn electric toothbrush is my busy pollinator every morning before I head to work.

.jpg)

Westbreen Primary garden go getters. (VIC)

.jpg)

Westbreen Primary garden go getters. said: The primary school vegetable garden, I look after with our students slowly starting to grow our winter crops.

Compost made from our classroom fruit waste adds wonderful nutrients you our garden where the students see it transformed from scraps to compost to garden to picking and eating the vegetables we grow.

.jpg)

Westbreen Primary garden go getters. said: Our asparagus bed flanked by 2 blueberry bushes and a lavender. Fingers crossed we can start harvesting asparagus in Spring. By bringing in pollinators with the help of our new flower pots, hopefully it will help us grow bigger more plentiful crops.

.jpg)

Westbreen Primary garden go getters. said: After a very successful first time growing loofah. We picked 15! The unseasonal warm weather has confused the plant and we have more growing! Best tip is make sure your trellis is very sturdy.

Dom Peters (QLD)

.jpg)

Dom said: My take on Eco brutalism. Mixing grasses, fern and moss with flowing Silver Dichondra, Cousin It and Scarlet Boganvillea. Cineraria, Red Flash Lotus to accentuate the levels

.jpg)

Dom said: Scarlet Boganvillea in front of Native Purple fountain grass.

.jpg)

Dom said: Making use of the shade to grow moss

Mrs Gardner (NSW)

.jpg)

Mrs Gardner said: Sleepy winter flower beds generously mulched with autumn leaves, nestled between pretty, wattle wood chip paths. Even after a light frost, the baby pincushions and everlasting daisies are still happy, slowly growing, awaiting the warmth of spring!

.jpg)

Mrs Gardner said:

‘Paper Daisy- Pink and White

Everlasting’

Rhodanthe chlorocephala

This Australian native daisy seems to be quite happy growing in my (temperate) winter flower garden!

.jpg)

Mrs Gardner said: Young Red Acre cabbage plants in a bed of autumn leaves. The pests aren’t a problem in this cooler weather, and they should be nice and sweet when I turn them into delicious purple sauerkraut!

Jenny (SA)

.jpg)

Jenny said: 'Up the garden path', a feel of waiting for Spring! Espaliered fruit trees along the fenceline are waiting to fruit, late-season sunflowers are inching along, garlic is growing patiently and in the background, golden asparagus fronds will be pruned to give way to bare earth soon. Capsicums can't be seen in the back garden bed but are overwintering and continue to ripen.

.jpg)

Jenny said: My favourite Snapdragons in bloom in the garden bed next to the sandpit, with carnations to each side and Cosmos self-seeding. Spring wildflowers and sweet peas pending on the trellis.

.jpg)

Jenny said: Under the insect netting: kohl rabi beginning to swell, Mache is thriving in the 20% UV filtering; its nutty flavour is coming through and I can eat it without having to worry about 'grubbing' for caterpillars or moths first.

Kool Garden (VIC)

.jpg)

Kool Garden said: Growing from seed.

The two Avocado plants started off as an experiment to develop roots. They were left in water for much longer than they should have before being planted into soil outside. This is their second winter outside, and most of their growth has happened during the last 6 months. With minimal care and a lot of neglect they've manages to survive. It just goes to show the tenacious nature of nature.

May (WA)

.jpg)

May said: I'm new to this gardening as a newbie housewife as well.

I wanna show you our humble raise garden.

With wild rockets, mustard leaves, and more leaves.

We got help from our little friends eating the weeds I've plucked and let them have some slaters.

.jpg)

.jpg)

May said: I love how are garden has grown into a luscious greens.

.jpg)

Congratulations to this months winner Renae K in SA; we loved seeing Hughie, Pip and Indy all handing out together in the garden!

Poppy Gnomes (QLD)

.jpg)

Poppy Gnomes says: This is Rani! A very beautiful girl, who LOVES to dig holes throughout the lawn and steal all the strawberries (see second picture where she was caught red-handed). She also loves sunbathing outside with all the flowers and having a good sniff around the veggie patch.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Bronwen (VIC)

.jpg)

Genevieve says: This is Pipin Cat, and she loves to join me outside in the garden. Her favourite hobbies include playing in dirt, eating dead twigs off my plants, chasing leaves and taking a snooze in my pot plants, regardless of any plant growing within. She enjoys snoozing in pots so much that I have brought a pot containing failed ranunculus from last season inside for her to snooze in. I’m sure they failed because it was her favourite snooze spot last year.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Tammy Gloster (VIC)

.jpg)

Tammy Gloster says: Wanda helping with the pruning

Meg (VIC)

.jpg)

Meg says: My reliable little friends are always there…under a lettuce leaf, visiting the zinnias or popping out of a zucchini flower.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sally K (VIC)

.jpg)

Sally K says: Gracie enjoying the morning sun amidst the kangaroo paw.

She doesn't mind getting her own paws dirty helping mumma in the garden either!

Romeo (VIC)

.jpg)

Romeo says: My goats Faunus & Amalthea (destroyers of blackberry); ducks Jup & Tess (snail and slug patrol), and dog Epona (digger of holes).

Pamster (VIC)

.jpg)

Pamster says: Doug is my Parson Terrier, there is no show without punch. We are starting from scratch on our new block so lots of earth works going on. This particular drain is for one of our water tanks that will Water the veggie patch and chooks. It was a shame I couldn’t send the video of this work, Doug was convinced there was something in the pipes he was hilarious with his head up the pipe, biting and shaking it.

Cookie (the kookaburra) comes everyday for a visit. My garden is only just being created so there is lots of work going on creating new beds, poly

Tunnel drainage etc. Cookie is fearless he comes in close and watches my every move. He is great company.

.jpg)

Renae K (SA)

This months winner.

.jpg)

Renae K says: Hughie, my little poddy lamb was a great companion in the gardens. Initially he was freely roaming around as I planted seedlings. But then the seedlings started disappearing! Both Pip and Indy kept a close eye on him, but couldn’t stop his grazing behaviour coming through.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Mountains harvest (NSW)

.jpg)

Mountains harvest: These are our helpers in our garden. Jean, Jet and Milly in first photo. Milly and Lulu in the second and Dot in the third photo. They are extremely helpful. Us and the neighbours that are looking in our garden, love them helping in the garden. Scratching the soil and leaving blobs of good fertilizer. We love them, they are a good bunch.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Dinah C (NSW)

.jpg)

Dinah C says: These are some of the regular visitors who help us with pest control or soil aeration!

.jpg)

Naomi Green (SA)

.jpg)

Naomi Green says: My beautiful ladies (Buttercup, Marigold, Rose, Tulip, Bluebell and Snowdrop) are always out helping me in the veggie patch. Most the time they are helpful helping aerate the compost heap, picking up the bugs and weeds and sometimes they are a little less helpful stealing my raspberries and tomatoes and eating odd seedlings but I love them and they are worth the missing raspberries.

.jpg)

Sian (QLD)

.jpg)

Sian says: The Foreman, busy at work

Reid Homestead Dream (NSW)

.jpg)

Reid Homestead Dream says: Max spends a lot of time making sure birds, leaves, and cars passing by do claim the backyard and all the plants. It’s only far he is represented.

Two acres and us (NSW)

.jpg)

Two acres and us says: Can you spot the dog?!

Crazy Daisy loves autumn leaves.

Denise (SA)

Denise says: Cooper my Burmese gardening friend testing my patience in my imatiens pot.

Rel (VIC)

.jpg)

Rel says: Luna is great at deadheading the flowers and loves to help dig the vege patch ready for winter planting.

A nap, using her tiger toy for a pillow, is needed after a big morning in the garden. Mum then sneaks back out to repair the damage and get some gardening done!

.jpg)

.jpg)

Simone Baker (TAS)

.jpg)

Simone Baker says: These little girls follow me everywhere in my garden, they love to have bantam dust baths close by where I’m working sharing their dust with me and even wanting to help dig up the dirt for me too, sometimes they are a bit to helpful and need a little shoo away.

Michaela (WA)

.jpg)

Michaela says: Our lovely Buff Silky Rooster Eagle - doing his thing in the garden and White Fluffy about to scratch in the fallen leaves and mulch in our orchard.

.jpg)

Zen (QLD)

.png)

Zen says: Young Masters Hook and Licorice are not only great company in the garden but also very helpful. They assist me with bug control, fertilizing and one of their favorite hobbies - turning mulch (often out of the garden beds, but they are young and still learning the finer points of gardening)

.png)

Tessa (VIC)

.jpg)

Tessa says: Millie, my golden cocker spaniel pup, loves 'helping' in the garden. Digging, weeding, sniffing and keeping me company are ways we enjoy our time in the garden.

.jpg)

Macca (NSW)

.jpg)

Macca says: The best gardening companion that a gardener could have.

Celia Collins (VIC)

.jpg)

Celia Collins says: This boobook owl has been roosting in our Japanese Maple nearly every day for the past 2 months. When we walk under the tree he never flies off but just looks at us quizzically to see what we are up to, every night he takes off, presumably to hunt but is usually back in the same spot the next morning. Of course I am saying 'he' but could very well be 'she'!

Gaily Snaily (NSW)

.jpg)

Gaily Snaily says: Rainbow Lorikeet in the red eucalyptus tree, making alot of noise, letting his presence be known.

Love them in the garden & always in pairs, they are naughtty & nice

Monarch Butterfly caterpillars 2 on the milk weed. Love having the beautiful cocoons hatching in the garden on other plants never on the same plant they feed from. Butterflies are graceful & busy all the time, love, love them

Thank you for choosing my garden

.jpg)

Fungus'eating ladybird. Helpful insect, adults feed on black mould & other fungi.

Good friend in the garden.

Kez (SA)

Kez says: Pussy cat is Queen Mimi the first . Ike and Tina the lizards ( they argue a lot haha ) and spider boy !! The first one rolls around everywhere and smells the flowers and the other three eat pests . All are welcome

Darren (WA)

.jpg)

Darren says: Missy's favourite thing about our garden is finding the spaces in between - the little dog-sized patches where plants don't grow, or where she's cleared a place for herself. Is there anything better than curling up in the winter sun? We love that she can enjoy these spaces, it makes our garden truly feel part of our home.

Maggie on the other hand is a digger and chewer. Her white fur gives away exactly what she's been up to, and those ears don't quite fit neatly in a pot. You could say she loves the garden more than the garden loves her.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Kristy-Ann (QLD)

.jpg)

Kristy-Ann says: Pleased to see the pest control patrol is on the job. This young butcherbird is demolishing the grasshoppers that eat my plants. He and his buddies, who get black and white uniforms when fully trained (magpies, magpie lark and butcherbirds) are very effective at controlling pests in my garden.

We also have the rainbow lorikeets who like to dine at the birdie bistro and splurge or on nectar cocktails in the surrounding trees, they bring the party to the garden.

And when it's warm, good old Harry can be counted on to be lounging about somewhere. I can him a racing stripe skink because of this awesome line green stripes, but I think he's actually a comb-earred skink. There's been several generations of Harry and Harriet popping their heads out to say hi, whenever it's nice and warm.

Scissorhands (NSW)

.jpg)

Scissorhands says: Zurich the corgi would come for a cuddle but he prefers the comfort of indoor where he can keep an eye on his food.

On the other hand, his bff Q the sheltie is the garden supervisor who likes to micromanage his pawrents. He is often found rolling on the grass and enjoying the ever-changing scent of the seasons.

Dianne (NSW)

Dianne says: 1. Introducing my favourite Garden Buddies! This is a full-grown Dwarf Eastern Green Tree Frog! There must be hundreds of them in various gardens that I planted over the last 7yrs. This one is sitting in a Day Lily, with which they seem to love & have a symbiotic relationship, helping pollinated the flowers &, in turn, get rewarded by catching the pest s that eat the flowers. If you are familiar with Day Lilies, you can see these frogs are tiny! Females can reach a maximum size of 25–30 mm, while males may only reach 20 mm when fully grown!

2. This is 'Tom' who assists (sometimes) being a Garden Helper with 'Mia' but usually can be seen keeping various decorative cane baskets about the place warm & ready for cut flowers I may take inside or just chillin' out conserving his energy being a garden ornament! He also was a Rescue Kitty at the same time of 'Mia', but he had was so thin & dehydrated I didn't think he'd pull through. He's also now 12yrs old.

3. This is 'Mia' surveying all she can see from a high fence post at my new address out of town. 'Mia' is a rescue kitty & was bought to me by the local Ranger as a tiny kitten when he found her in a gutter. I had just lost my old 17yr old cat from an age-related illness, that was the exact same colour!

'Mia' assists me in the garden with constant smooches, distracting me so I don't see her favourite weeds & reminding me it might be time for my cuppa & bikkies for her!

She's been my garden assistant now for 12yrs! You might say 'From Gutter Waif to Gardening Guru'!

Tamara (QLD)

.jpg)

Tamara says: After our dog of 13 years passed away, being in the garden was hard. I missed her faithful companionship as she followed me about. We weren't ready to have another dog, but one day I decided to welcome two gorgeous little bantam chickens to share our world. They are Elsie and Esme and they are everything I could have hoped for. They are the greatest of friends and I love watching them do their chicken thing and cluck softly about. They love a treat and a cuddle, and while they don't replace our beautiful old dog, they do make us smile once more.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Aimee (WA)

Aimee says: These are out pet geese, who reside in a yard of their own beside my vege patch. They also have access to our oak/truffle paddocks, but have their pond and get fed in their own yard. The excess trimmings, cuttings, and outgrown plants etc tend to end up in a pile in their yard to get burnt, by the end of Autumn the pile is huge.

The photos here were taken after the initial burn, when I had put a heap on the pile that was too green to burn....the geese were most interested and spent the next week investigating it and eating what they could - even from the top of the pile!

They are very cheeky - I only managed to harvest about a third of my tomato crop this year because they kept breaking in to the vege patch, till I finally worked out how they were escaping.

Every time I go in there to weed, water etc they line up in a row and watch, waiting for any pecked fruit or greens for a treat.

Marmaduke - the grey goose, thinks he is in charge of the yard - he is always first in line for any vege scraps, but the rest of the white flock aren't shy in fossicking for their share!

Joanne (NSW)

.jpg)

Joanne says: Helpful and bright, and all things nice in mine and my daughter’s gardens.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Dorothy (VIC)

Dorothy says: Kaiser was his name, A very well loved family member. He didn't just dig his bones in the ground he made crateres for them.He was always with me while l was gardening.Passed away 2019 aged 10, still sadly missed..

Tangerlyn (VIC)

.jpg)

Tangerlyn says: After filling my Garden with Salvias of all varieties and colours finally l have created a home for my favourite birds in my Vermont garden, the Spine Bill.

Penny (VIC)

.jpg)

Penny says: Meet our resident ringtail possum "Dale" (the kids named him, not me!)He loves to hang out in our garden, mostly during the late arvo into early evening, and is very friendly. We've made a nestbox for him in one of our larger trees, which he's found comfy and helps him feel protected. Thankfully, Dale leaves the edibles I've planted alone - preferring to eat the callistemon flowers and new growth, as well as eucalypts further down the street. He is a wonderful little gentle friend to have share our area.

.jpg)

Cathryn (VIC)

.jpg)

Cathryn says: Bear and Gina are the guardians of all they survey. Astrid has just begun her idyllic life in the chicken Hilton

.jpg)

.jpg)

Purple Nat (VIC)

.jpg)

Purple Nat says: My little Sydney, she’s my constant companion in the garden.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Cottage garden (NSW)

.jpg)

Cottage garden says: Butters the cat enjoying the tea room, kylo the dog romping on the garden path, bunny staying out of the garden

.jpg)

.jpg)

Lauren C (NSW)

.jpg)

Lauren C says: Mr Hammy, Sabrina, Arabella and Pepper love to hang out in this pot and sunbathe. Sometimes there’s more chickens than soil!

.jpg)

.jpg)

Nature-haven (QLD)

Nature-haven says: Hi

These are some of my garden friends.

When we moved to our home the yard was just grass with no birdlife or insects to find. We've planted masses of flowers, grasses and native plants and now we have so many garden friends such as birds, lizards, insects, frogs and even some Tree Snakes. Here are some of our friends that visit.

A pair of Pale Headed Rosellas visit our garden daily to feast on seeds they find among our many plants and flowers.

A Lesser Wanderer butterfly also loves visiting our garden to find nectar in the many flowers we have.

My last garden friend is one of our resident Little Wattlebirds. A family of three visit our garden each day to splash about in any of our seven birdbaths. They splash around so much that we have to refill the baths everyday. They just seem to love our garden and its Grevilleas and baths. They are a joy to watch.

Thanks.

Jojo (QLD)

.jpg)

Jojo says: Raven and Misty. Raven came to us from a friend as a day-old chick. In her first few hours, our friend rescued her from being trapped inside a hard, sticky egg-membrane. Even with utmost care, some of Raven’s tiny new feathers were stuck into the membrane, so she was a little less-feathered than the others, and the smallest. But she survived the first night, and then thrived. Since then, she has been the most curious, most friendly, most persistent, smartest, and the best layer we have. She is a very naughty chook who gets into everything, but we forgive her! Our dog Misty loved watching the chickens grow up, but Raven fearlessly used to peck at Misty’s hair to see if it was edible! Dear gentle Misty put up with a lot! Now Misty knows Raven isn’t supposed to get into the garden unless we say so, and is keeping a close eye. Misty is a little timid of Raven – now she’s not a chick anymore, but will give her a gentle nudge along if needed. But Raven especially loves the mustard greens here, and will try, and try again!

.jpg)

.jpg)

Newly Budding Green Thumb (WA)

.jpg)

Newly Budding Green Thumb says: This is Gooseberry, the porch cat. He showed up several weeks ago and has been helping supervise while we do our spring planting. His only request is that we take frequent breaks to give him pets and attention. He loves to roll around in the grass next to my raised planters.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Jen (NSW)

.jpg)

Jen says:

There’s a little group of ladybugs in my garden I’ve come to think of as The Dotsquad. They spread out across the plants, especially around the roses and kale, where aphids like to sneak in. The ladybugs aren’t flashy about it, just going about their work, keeping the garden in balance without much fuss.

They’re not perfect, of course. Sometimes they disappear for a bit, and I’ll catch them napping in flower petals or tucked into shady corners. But I like that about them. They do what they need to, in their own time, and the garden is healthier for it.

It’s become a small habit now, checking that branch in the morning to see if they’re still there, tucked in like a little community. It’s a quiet kind of joy.

Preventing Pests and Diseases

One of the most compelling reasons to remove declining plants is to actively prevent the spread of pests and diseases. Plants that are nearing the end of their natural life often experience stress, which can weaken their defences and make them more susceptible to various issues. These weakened plants can then become attractive breeding grounds and readily available food sources for unwanted pests. For instance, a tomato plant that has finished its productive phase, characterised by yellowing leaves and a decline in fruit production, might attract aphids, whiteflies, or other common garden pests. These pests can then easily migrate to healthier plants in the vicinity, causing further damage and potentially impacting the overall health of the garden.

Similarly, plants that are in decline are often more vulnerable to fungal diseases. For instance, powdery mildew, a common fungal disease, especially during periods of high humidity, can readily colonise stressed plants. This disease, recognisable by its white, dusty coating on the leaves, can rapidly spread to other susceptible plants, including cucumbers, zucchini, and pumpkins. Promptly removing the affected plant helps to contain the problem and protect other healthy crops from infection.

Enhancing Visual Appeal

Beyond the crucial aspect of plant health, removing spent plants offers a tangible improvement to the visual appeal of a garden. A garden that is filled with plants exhibiting yellowing foliage, a straggly appearance, or signs of decay can detract significantly from the overall beauty of the outdoor space. The removal of these tired elements can instantly rejuvenate the look of garden beds, creating a more visually pleasing environment. Consider annual flowers that have passed their peak; while they may have once provided a burst of vibrant colour, they often become leggy and produce only a few sparse blooms as they near the end of their life cycle.

Maximising Garden Productivity by Making Room for New Plants

Removing plants that are past their best is also crucial for making room for new, more productive plants. Every garden has limited space and allowing tired or unproductive plants to remain prevents you from growing new crops. For example, once a vegetable plant like a tomato or cucumber has finished producing its harvest or is succumbing to disease like mildew, it continues to occupy valuable space and resources. By removing these spent plants, you create opportunities to sow new seeds or plant seedlings that are in their prime, ensuring a continuous cycle of growth and harvest throughout the gardening year. This practice allows you to maximise the productivity of your garden and enjoy a greater variety of plants.

Improving Airflow and Sunlight

Dense, dying, or unproductive foliage can also impede crucial airflow and block sunlight from reaching healthy plants growing beneath. Restricted airflow can lead to increased humidity around plants, creating an environment conducive to the development of fungal diseases. By removing old, overcrowded plants, gardeners can significantly improve both air circulation and the amount of light that reaches the remaining healthy plants, fostering a more favourable environment for them to thrive.

Preventing Self-Seeding

Managing plant propagation is another important consideration in maintaining a well-kept garden. While the self-seeding of certain annual flowers can be a welcome occurrence, other plants that are past their prime may release seeds that the gardener does not necessarily want spreading throughout the garden. Removing these plants before they reach full seed maturity can help gardeners retain control over what grows in their garden beds and prevent the emergence of unwanted seedlings in unexpected locations. This proactive approach to managing self-seeding contributes to a more organised and intentional garden design.

Enhancing Soil Health

The act of removing a plant that has reached the end of its productive life presents an excellent opportunity to enhance the soil for future plantings. After removing the old plant, consider incorporating compost or well-rotted manure into the soil. This practice helps to replenish essential nutrients that may have been depleted by the previous plant, improving the overall fertility and structure of the soil for subsequent growth. Furthermore, if the removed plant exhibited signs of disease, it is generally advisable to avoid planting the same type of plant in the same location for a certain period. This precaution helps to reduce the risk of soil-borne diseases persisting and affecting new plants. Implementing crop rotation practices can also further minimise the potential for disease buildup in the soil over time.

Common Examples

Consider these common scenarios in a garden to further illustrate the benefits of removing spent plants:

- The Tired Tomato Plant: After several months of producing delicious tomatoes, the plant may begin to look exhausted, with yellowing leaves and minimal fruit production. At this stage, it has likely reached the end of its natural life cycle and is best removed to make room for a new round of planting.

- The Mildew-Covered Cucumber: As previously mentioned, powdery mildew is a frequent issue on cucumber plants. Removing the affected plant promptly is essential to prevent the fungal disease from spreading to other plants in the garden.

- The Straggly Annual Flower: That petunia or zinnia that once provided a vibrant splash of colour may now appear tired and produce very few flowers. Pulling it out will create space for planting fresh, vibrant annuals for the next season, ensuring a continuous display of blooms.

- Bolted Vegetables: Vegetables such as lettuce and spinach tend to "bolt," sending up a flower stalk, in warmer weather conditions. Once this occurs, the leaves become bitter and less palatable. It is best to remove these bolted plants to make space for new sowings of more desirable crops.

While it may evoke a touch of melancholy to bid farewell to a plant that has been cared for, it is important to recognise that removing plants past their prime is an indispensable element of the natural gardening cycle. It is an act of responsible garden management that contributes significantly to preventing pest and disease outbreaks, enhancing the aesthetic appeal of the garden, maximising productivity by freeing up space, and ensuring the ongoing health of your garden. Gardeners should not hesitate to respectfully remove tired plants, making way for new life and the promise of vibrant growth in their patch.

Fortunately, there's a simple, effective, and inexpensive solution: mixing your seeds with sand before sowing. This technique uses sand as a bulking agent, making seeds easier to handle and distribute evenly, whether you're dealing with minuscule seeds or covering broad areas.

This article will explain why sand mixing works so well, guide you on choosing the right sand (and what to avoid), suggest mixing ratios, and provide practical steps for using this method effectively.

Why Mix Seeds with Sand?

Mixing seeds with sand increases the volume you're working with, making a small quantity of seed easier to handle and distribute evenly across the soil. This simple principle offers significant benefits in two common scenarios.

Handling Tiny Seeds

Seeds like poppies, foxgloves, petunias, lobelia, oregano, thyme and mint can be incredibly small. This presents several challenges:

- Handling Difficulty: They are hard to pick up and easily lost.

- Over-sowing: It's easy to sow them too thickly, leading to crowded seedlings competing for resources.

- Waste and Thinning: Overcrowding wastes seed and requires careful thinning, which can damage the remaining seedlings' roots.

Mixing these tiny seeds with sand makes the mixture easier to grasp and sprinkle thinly. The sand separates the seeds, promoting better spacing from the start. Lighter coloured sand also provides a visual guide against darker soil, helping you see where you've sown.

Even Coverage for Large Areas (Broadcasting)

Achieving even seed distribution when establishing a wildflower meadow, sowing a lawn, or planting larger crops can be difficult. Hand scattering or using spreaders often results in uneven patches.

Mixing seed with sand adds bulk and weight, regulating flow from spreaders and making hand broadcasting more controlled and uniform. Dividing the mix in half and applying it in perpendicular passes (e.g., North-South, then East-West) further improves evenness.

The sand's visibility helps track coverage, and its weight helps seeds settle onto the soil, resisting wind drift and improving crucial seed-to-soil contact for germination.

Choosing Your Sand Wisely (and What to Avoid)

The goal is to use a sand that provides bulk and separation for easier sowing, without creating problems like compaction right around the seed.

Recommended Types:

- Horticultural Sand: Specifically processed for garden use, it's gritty, washed, graded, and often lime-free (pH neutral), making it a safe choice. Find it at garden centres and nurseries.

- Builder's Sand (Coarse): A common, economical option from hardware stores and building suppliers. Ensure it's coarse (sometimes called concrete sand), not the fine sand used for bricklaying mortar. Coarse builder's sand can contain silica dust, so consider wearing a mask if handling large dry quantities.

- Coarse Sand / Grit: These terms refer to sand with larger, angular particles. The angular shape helps prevent the particles from packing too tightly immediately around the seed. Available at building suppliers or landscape yards.

Whichever sand type you choose it's import to make sure it's washed and free from fine silt, clay, salts, weed seeds or other contaminants. Horticultural and concrete sand are usually washed so are usually the best choice.

Sand to AVOID:

Play Sand / Sandbox Sand / Fine Sand: Do not use this for mixing with seeds. The particles are very small and often rounded. When wet, they pack together tightly, creating a dense, airless environment right around the seed that hinders germination and root growth – the opposite of what's needed.

Alternatives to Sand

If suitable coarse sand isn't available, other fine, inert, or organic materials can serve as carriers:

- Vermiculite: Lightweight, holds moisture and air well, good for tiny seeds.

- Perlite: Primarily adds aeration.

- Fine, Sieved Compost or Seed Raising Mix: Can add nutrients, but must be fine, free-flowing, and weed-free. Both are best used dry.

The principle remains the same: add bulk for easier, more even distribution without negatively impacting germination.

Getting the Mix Right: Sand-to-Seed Ratios

There's no single perfect ratio; it depends on seed size, area size, sowing method, and personal preference. Feel free to experiment!

As a starting point, for handling tiny seeds, a ratio of 1 part seed to 4-10 parts sand (by volume) is recommeded. Some gardeners use a simple pinch of seed to a tablespoon of sand for small quantities. This dilution makes handling easier and promotes better spacing.

For broadcasting over large areas, a higher proportion of sand is typically used to add sufficient bulk for even spreading. Ratios anywhere from 1 part seed to 5 parts sand, up to 1:20, are common. The key is to add enough carrier material to allow for controlled distribution by hand or spreader.

A higher sand ratio (e.g., 1:20) results in a more diluted mix, making it easier to achieve sparse sowing. A lower ratio (e.g., 1:2) gives a more concentrated mix. Adjust to suit your specific needs.

Simple Steps for Mixing and Sowing

- Prepare Your Soil: Ensure the area is weed-free. Loosen the soil and rake to a fine, level tilth. Remove large debris. Lightly pre-watering helps seeds stick.

- Ensure Sand is (Mostly) Dry: Dry or slightly damp sand flows best, especially for spreaders. Slightly damp sand can help seeds adhere for hand broadcasting but avoid wet, clumping sand.

- Mix Seed and Sand Thoroughly:

- Small quantities: Use a clean jar, bowl, or simply add the sand to the seed packet. An old spice shaker works well as an applicator.

- Larger quantities: Use a clean bucket, tub, or wheelbarrow. Mix well by hand (use gloves if desired) or with a trowel. For very large areas, mix with a shovel on a clean tarp.

- Scatter the Mixture Evenly:

- Hand Broadcasting: Use a consistent, sweeping motion. Walk systematically. Use the perpendicular pass method for large areas. Practice with just sand if unsure.

- Using a Shaker: Gently shake over drills or seed trays.

- Pinch and Sprinkle: For very small sowings simply pinching and sprinkling seeds is also an effective method.

- Using a Mechanical Spreader: Calibrate first according to instructions, starting with the smallest setting and testing on a tarp. Walk at a steady pace.

- Cover Lightly & Ensure Seed-to-Soil Contact: Crucial for moisture uptake.

- Gently rake soil over seeds. Aim for a covering depth similar to the seed's diameter – tiny seeds need very little or no cover. Pressing them firmly onto the soil might suffice.

- Alternatively, sift a fine layer of compost, seed mix, or more sand over the area.

- Gently firm the soil using a rake, or your hands.

- Water Gently: Use a fine spray immediately after sowing. A watering can with a fine rose or a hose on a mist setting is ideal. Keep the area consistently moist until seedlings establish.

***

Mixing seeds with sand is a simple, low-cost way to overcome the challenges of handling tiny seeds and broadcasting evenly over large areas. Sand acts as a carrier, improving distribution and spacing, which reduces thinning, saves seed, and leads to healthier plants. It’s a straightforward technique that can significantly improve your sowing success and might just become a regular part of your gardening routine.

.jpg)

And now, we're excited to announce the winner of the $100 store credit: Elina Skliarenko from Victoria!

Elina's winning entry, "Bug Snug" really impressed us. Her idea of building a simple shelter using natural materials like bark, pinecones, and sticks to attract helpful bugs is a fantastic way to support a healthy garden ecosystem. Congratulations, Elina!

Read on below to see all the other great tips and tricks that were submitted – you might just find your next brilliant gardening idea!

***

Genevieve Locke (WA)

.jpg)

Genevieve says: Sewing seeds in toilet roll tubes. This is a great way to sew seedlings that don't like their roots to disturbed eg Zinnia and Sweet Peas and also stops your seedlings disappearing when you plant out due to critters in the soil eg cut worm which bites the seedling off at the base. Make 4 even slits half an inch at one end then fold over like the lid of a box. Once seeds have sprouted you can open the bottom or just leave if roots are coming through. Plant the tubes leaving them half a inch above the soil. The rolls will breakdown. I keep mine in recycled meat trays packed in fairly tight so they stand up and water from the bottom. Keep watch for drying out in hot weather as the cardboard draws the moisture

.jpg)

.jpg)

Genevieve says: Saving seed from your favourite zinnias so they come out with same flower from previous year.

Place organza bags (buy from $2 shop or similar)over the bud before it opens. Zinnias can self pollinate. This method stops bees from pollinating the flower and changing its colour. Once the flower has dried up and changed to a crunchy brown pull the flower apart. I use a pair of long tweezers. The seeds should be hard . If you hold the seed between thumb and forefinger and press the seed should be stiff and not bend. I have had some amazing success and some disappointments where some did not pollinate but about 85%.

The lime and pink zinnia flower came from a bee pollinated zinnia 2yrs ago and this is the first one this yr from this method of saving seed. I got about 50 seeds from this plant

Rocket (VIC)

.jpg)

Genevieve says: I line a tray with plastic then place punnets in the tray and fill with water. This keeps your seedlings moist even in very hot weather for several days and saves watering time and frequently checking moisture.

Linda (TAS)

.png)

Linda says: Possum Scarer; From a couple of garbage bags, rags, fishing line and 3 sticks I made a Tassie Devil that can be pushed into the grass in my back yard or clamped to the rails on my front deck. It moves in the wind from side to side and scares the possums away

Mickey Vee (WA)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Mickey says:

A cracking idea!

An Egg-cellent Way to Keep Snails at Bay!

Looking for a cheap and eco-friendly way to protect your plants from snails? Save your eggshells!

Here’s how:

Pop the empty eggshells into your air fryer for 3 minutes to dry them out.

Once cool, crush them using a mortar and pestle into a fine, gritty texture.

Sprinkle the crushed shells around the base of your seedlings and garden plants.

The sharp edges deter snails and slugs without the need for harmful chemicals - plus, eggshells add calcium to your soil over time.

Great for your garden and the environment!

Tanya Afams (SA)

.jpg)

Tanya says: Rainwater tank keyhole garden.

.jpg)

Tanya says: Instead of having a crane lift out our old tanks, I drew up this design. 2 keyhole gardens from one tank. Top two rings are the main frame with a small piece cut for entry and flipped to become the middle. The bottom ring becomes the side walls of the key. Huge success on our clay soil. Now have a more friable soil in the tanks.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Tanya says: Very happy with these time saving raised seedling boxes I designed. Drew out the plan, put the frame together and hubby banged them up. I put them on an old welded frame so just at waist height.

Punnets and seedling pots dry out so fast. With the deeper soil in the boxes, allows soil to remain moist longer. I drilled holes in the wood to accommodate the arch protective netting tunnel so seedlings get a great start.

Paris (NSW)

.jpg)

Paris says: This is my budget seed raising set up, which sits on the verandah. I use old egg cartons and shells to plant the seedlings in

.jpg)

Paris says: When they’re ready I can place the egg or cut the square containing the sprout off and add to the bed where I want without risk of damaging the delicate roots. My ‘Greenhouse’ is a broken overturned clear storage bucket on a piece of corflute.

.jpg)

Paris says: I also have a small indoor version using only egg shells sitting in a clear egg storage container with a lid that I got for about $5 from Bunnings.

Sara (NSW)

.jpg)

Sara says: Make the birds in your garden your friends. I always leave a tasty treat or two uncovered for my Birdy friends to enjoy. They repay me 100 fold by catching endless caterpillars, grasshoppers and other pests. They never touch the harvest. The most effective hunters in my garden are the noisy miners and the butcher birds. We have families living and breeding in our yard. I could watch them all day long.

Angie Trewhella (WA)

.jpg)

Sara says: Beer in a shallow dish is the best slug trap there is! They prefer getting sloshed to eating my produce and the birds seem to enjoy a marinated treat!

Plant Addict (VIC)

.jpg)

Plant Addict says: Old shower caps make fabulous covers to stop drips in hanging baskets that don’t have plastic liners. If the elastic is too blown then a couple of stainless steel pegs work wonders. The colourful caps look great too!

Cas Jsa (QLD)

.jpg)

Cas says: Rat and Cat Deterrent, sometimes even possums. This tip has saved my corn and other vegies and fruits. Get a small container, either plastic or a small bottle with a tin lid. Punch a few holes in the lid. Fill the container half full of Citronella and put the lid back on. Sit the container in the middle of your garden or on top of the soil in a pot. Rats, mice, cats, and possums HATE the smell and will leave your crops alone. You can see here I've just planted pole beans and I have a tiny plastic container in the middle of the garden that is half full of citronella.

Elina Skliarenko (VIC)

This months winner!

.png)

Elina says:

"Bug Snug" – Creating a Cozy Haven for Beneficial Insects

To maintain a natural balance in the garden, it’s important to attract not only pollinators but also predatory insects that help control pests. That’s why I create "Bug Snug"—a cozy refuge where insects can live, breed, and overwinter.

A Bug Snug is not just a pile of twigs; it’s a true natural shelter where every creature can find its perfect hiding spot. It contains everything they need—bark with tiny crevices, pinecones, sticks, small logs with cracks where beetles love to hide, and even straw for extra comfort.

How to Make a Bug Snug

Creating a cozy corner for insects is easier than you think:

Build the frame. Take three (or more) long sticks—bamboo, hazel, or even eucalyptus will work. I used bamboo sticks and tied them together at the top to form a sturdy tipi. This serves as the foundation for the entire structure.

Secure it in the ground. Push the bottom ends of the sticks into the soil so the structure stands firm and steady.

Add natural filling. I carefully collect and arrange pieces of wood, dry leaves, wood chips, pinecones, straw, bark, and small branches to create a warm and safe home for insects and other garden creatures.

Welcome new residents. Now, I love watching as ladybugs, beetles, spiders, and even small lizards make their home in these cozy hideouts. The Bug Snug comes to life, filled with rustling sounds, tiny movements, and the vibrant pulse of nature itself.

A Bug Snug is not just a charming addition to the garden; it’s a vital part of the ecosystem. By creating these shelters, we support nature, reduce organic waste, and promote healthy soil.

.jpg)

Elina says:

Green Manure – Nature’s Way to Enrich the Soil

To keep my soil fertile and full of life, I actively use green manure—plants grown specifically to improve soil structure, enrich it with organic matter, and suppress weeds.

How I Do It:

After harvesting, I sow fast-growing green manure plants such as mustard, phacelia, clover, or lupine in my garden beds.

When they grow tall, I don’t remove them completely; instead, I cut them down and leave them as mulch on the surface or gently incorporate them into the soil to break down and enrich it.

Mustard helps cleanse the soil of pathogens, phacelia improves soil structure, and clover fixes nitrogen, making it available for future crops.

In autumn, I plant winter green manure crops such as rye or vetch, which protect the soil from erosion and, in early spring, become a rich natural fertilizer.

Thanks to green manure, my soil remains loose, fertile, and full of life, allowing me to grow abundant harvests without chemical fertilizers.

.jpg)

Elina says: Nurturing the Soil Microbiome – Healthy Soil Without Chemicals

The secret to a thriving garden is not just good soil—it’s the invisible life within it: bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms. Instead of simply feeding my plants, I focus on developing a healthy soil microbiome.

What I Do:

• I regularly use microbial inoculants like Popul8 and GOGO Juice, which contain beneficial bacteria and fungi that enhance soil structure.

• I apply Trichoderma and Bacillus subtilis, which suppress harmful pathogens and help plant roots absorb nutrients more efficiently.

• I cover the soil with mulch (straw, grass clippings, wood chips) to create the perfect environment for beneficial microbes to thrive.

• I avoid tilling the soil, preserving the natural relationships between fungi and plant roots.

With this approach, my plants become more resistant to diseases and drought, while my soil grows richer, healthier, and more fertile every year.

Heidi (VIC)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Heidi says: Full cycle - recycle - pea cycle

Growing sweet peas and eating peas such as sugar snap and snow peas are rewarding crops. After their final harvest I pull out the spent plants and store them in a tub over summer where they dry out. Then in autumn, when I have planted the collected seed and other winter veggies, I use my organic homemade pea straw mulch to keep the soil warm.

Moonie (NSW)

.jpg)

Moonie says: Grow snail and slug vulnerable flower seedlings in a pot then move pot into the flower border.

.jpg)

Moonie says: Protect snail and slug vulnerable seedlings in a cloche made from old plastic bottles. Compare size of unprotected versus protected bok choy.

.jpg)

Moonie says: Lazy seed-raising method for time-poor gardeners using coriander (which enjoys simple direct sowing). Clear and prepare a bed, scatter seed, muss into soil with hands. Let nature do the rest.

Zane B (WA)

.jpg)

Zane says: When planting several varieties of seeds in pots, it is so easy to forget which pots have which seeds. But I found an easy way to tell. I line up a row of pots of one variety and make a marker flag for the start of that row, and I don't have to buy anything special to do it. Whenever I cook skewers of meat on the barbie, I save the used skewers after dinner and rinse them off. Then, when it is seed planting time, I take one of the skewers, cut off the top of a seed packet from the Seed Collection with the name on it, tape it to the skewer, and voila! I little flag to identify what's planted. Here you can see the one I've made for the Broccoli - Green Sprouting Calabrese seeds.

Jen (NSW)

.png)

Jen says: If birds keep stealing your strawberries before you can pick them, try placing a few small red-painted rocks around the plants before the berries ripen. Birds will peck at the rocks, thinking they're real fruit, then lose interest when nothing happens. It’s a simple way to protect your harvest without using nets or scare tactics.

]]>Thank you to everyone who took the time to share their hard work and the fruits (and vegetables, and herbs, and flowers!) of their labour. We've been so impressed by the variety and dedication on display, and we hope you enjoy browsing through this collection of wonderful harvests as much as we have. Get ready to feel inspired and perhaps even a little hungry!

Stay tuned for more exciting competitions and opportunities to share your gardening journey with our community! Happy gardening!

***

The Seed Bomber (VIC)

.jpg)

The Seed Bomber says: A pot full of heartsease with their canine guardian in the background. While he does do a good job chasing away birds that dig up our pots, he has also developed a taste for young pansy leaves and flowers!

.jpg)

The Seed Bomber says: Sweet basil grew in abundance this year.

.jpg)

The Seed Bomber says: Tomatoes were not nearly as plentiful but we got a few kilos of the cherry variety.

Syberia (NSW)

.jpg)

Syberia says: Accidental sweet potatoes, thought we had harvested them all but apparently not.

.jpg)

Syberia says: A massive harvest of a volunteer tomato plant that grew in my sidewall. I had a very happy 7 year old whom devoured all of them in 3 days

.jpg)

Syberia says: Small harvest after going away. We were very happy with our Small abundance. The chillies are Scotch bonnet and Jalapenos.

Toni Porter (TAS)

.jpg)

Toni says: My dining table full of beautiful colour- Tomatoes in various stages of ripening (I pick them as soon as they get a hint of colour and they ripen beautifully inside, to avoid pests), Zinnias which I grew for the first time this year, and Tasmanian Pepperberry, drying in a bowl - I use the leaves and berries for cooking tea

.jpg)

Toni says: Cafe au Lait Dahlias and Jude the Obscure Roses looking beautiful together. I get many flushes these over many weeks. My very favourite Rose and Dahlia compliment each other so well!

Anke Anna (NSW)

.jpg)

Anke says: Cucumbers taking over my washing line

.jpg)

Anke says: Scarlet Runner Beans with first bean harvest

.jpg)

Anke says: Tamarillos, still growing

Elina Skliarenko (VIC)

.jpg)

Elina says: Summer painted the garden beds, weaving bright colors and fragrances together.

In my palms, warm from the sun, rest the first apples—most cherished, crisp, and juicy. Their scent awakens childhood memories, of grandmother’s apple orchards where each fruit was a sweet secret hidden among the green leaves.

The cucumbers, rough and crunchy, still hold the coolness of the morning dew. They are like tiny forest hedgehogs, curled up among the tangled vines. The eggplant, smooth and mysteriously dark, hides beneath the foliage—a drop of night in this radiant, sunlit world. Tomatoes have soaked up the summer’s sweetness, and strawberries gleam like scattered rubies, luring with their sugary promise.

And among this abundance—flowers. As if they have gathered all the shades of summer: sunlit yellow, fiery red, deep crimson. Their petals tremble in the gentle breeze, weaving the garden’s fragrance into the morning air.

I gathered all this richness into one bouquet—summer cradled in my hands. Not just a harvest, but a symphony of nature, where every fruit and every flower is a note in the great melody of life. This morning will stay with me—the scent of fresh apples, the cool touch of cucumbers, and the silky whisper of flower petals.

.jpg)

Elina says: The plums have ripened in the garden. They hang in heavy clusters on the branches, warm from the sun, their deep purple skin hiding juicy, golden flesh within. A single touch, and it feels as if they are ready to tumble right into your hands.

Their taste is like childhood—like carefree summer days, like a gentle breeze in the shade of the trees. There is something magical about them, as if each plum carries a little piece of the sun’s golden smile.

.jpg)

Elina says: I stepped into the garden barefoot, letting the cool grass gently embrace my feet. The night’s dew had yet to dry, and the morning sun was just beginning to spill its golden light, awakening the garden. The air was filled with the scent of fresh greenery, blooming herbs, and damp earth—pure, alive, infused with the breath of summer.

I didn’t take a basket. Instead, I simply gathered the hem of my shirt and filled it with the morning’s harvest—just as I used to in childhood. A young zucchini, bumpy cucumbers still cool and rough to the touch, a sun-kissed pattypan squash, tomatoes the color of deep amber… All of it—fruits of care, warm days, raindrops, and the gentle touch of nature.

Tamara (QLD)

.jpg)

Tamara says: After a tough day at work, I found so much joy just wandering around the garden collecting these beautiful little blooms. It was a gentle reminder of how healing nature can be.... zinnia, cosmos and dahlia...

.jpg)

Tamara says: The colour!!

Ry duncan (NSW)

.jpg)

Ry says: Over 3kg of cucumbers! With more still on the two plants!

.jpg)

Cass (QLD)

.jpg)

Cass says: Little Miss Avery helping to harvest our bumper crop of Dutch cream potatoes in our plot at the community gardens. They were so tasty roasted, mashed and added to soup.

.jpg)

Cass says: Carrots grown in a raised bed at home. Ready for washing and cooking. - destined for the soup pot. I experimented with three different varieties of carrots and chantenay was a clear winner!

.jpg)

Cass says: Had a pretty good crop of button squash this season. Not sure how they ended up stripy, I was only expecting yellow ones - cross pollination maybe? They are very pretty looking and taste fabulous in stir fries.

Reid Homestead Dream (NSW/ACT)

.jpg)

Reid says: Tomatomania! I have Cherry, Siberian, Tri star, Burnley sure crop and of cause Roma.

.jpg)

Reid says: The joy and satisfaction of plating up food you grew from seed is next level living. Early White Spanish onions, Nicola potatoes (very high yield), Every Season carrots and, Waltham butternut pumpkin. Mmmmm

.jpg)

Reid says: Just after a wander around the garden. Still bringing in tomatoes ( Cherry, Tri Star, Burnley, Siberian and, Roma) along with Utah celery, Sweet basil and, Triple Curled parsley. So much joy.

Kiara (TAS)

.jpg)

Kiara says: In this photo you're seeing a harvest from our little backyard garden. I'm a mum of two girls, aged 6 and 9 years old. We love spending time in the garden together, and my girls have helped to plant and harvest much of this produce. Here we have some Detroit beetroot, silverbeet, sprouting broccoli, kale, pineapple sage and others. My favourite part of gardening is watching my daughter's enjoy the harvest. They will go outside and, pick and eat tomatoes, lettuce, herbs straight from the garden.

Gloria M (QLD)

.jpg)

Gloria says: Flowers that delight me.

.jpg)

Gloria says: Beautiful hibiscus

.jpg)

Gloria says: Jade in all its glory

Leah Fitzmaurice (WA)

.jpg)

Leah says: Returning from an 18 day trip is always a nervous time for a gardener! Is anything still alive?

My gardens welcome home gift basket shown here.

.jpg)

Leah says: Our favourite game is hunting for "baby" pumpkins and getting excited as they turn into "big daddy" pumpkins. (Yes I know, it's a squash - but to my 3 year old everything is pumpkin!)

.jpg)

Leah says: What does 100 chillies look like? Shame the toddler can't handle spice, darn.

Nina (NSW)

This months winner!

.jpg)

Nina says: An early morning pick for my bouquet…some peachy zinnias, a few varieties of celosia and a pop of white and purple gomphrenas!

My first season growing flowers with intention, decided to start with these ‘easy to grow’ varieties, they all had fantastic germination and grew so well! Will definitely be adding more to my collection next season!

.jpg)

Nina says: A dried flower wreath made from a mix of statice, strawflowers, yarrow, globe amaranth and my absolute favourite, flamingo feather celosia!

I started growing flowers in earnest in 2024, with a lean toward varieties that are gorgeous both fresh and dried.

Dried flowers, like statice, are so nostalgic for me.

.jpg)

Nina says: Peach ‘Zinderella’ Zinnia

Caustin (WA)

.jpg)

Caustin says: I grow enough veggies for my partner and myself and plenty to take along to our local Saturday morning food swap. This is just some of the produce I snapped early one morning so I could put it on our local Facebook page to remind people that it was on.

I love my veggie garden…. I chat to the plants every morning while harvesting them.

.jpg)

Caustin says: I have had great success growing lovely capsicums. This one was a beauty. My plants overwintered and started producing early. What a bonus!

.jpg)

Caustin says: I put shade cloth over the veggie garden each summer. It really helps them deal with the heat. It cost a few hundred dollars to set up but is really worth it.

Pippy (SA)

.jpg)

Pippy says: I planted two small banana plants in my suburban Adelaide backyard. I wanted the leaves to steam foods in and never thought we would every see the fruit.They have gone bananas. We now have two large hands of bananas and they are delicious. We have used the leaves for steaming, the bananas in smoothies,cakes and snacking on, also the inner stem of the plant in our stir fries and curries. What a diverse plant. We love it.

AMO (NSW)

AMO says: These pumpkins are the result of burying kitchen scraps into my raised garden bed instead of composting as I usually do.

Experimenting & Second Chance Successes (SA)

.jpg)

Experimenting & Second Chance Successes says: Autumn harvest with the last of the cherry tomatoes (Cosmic purple), yellow and red Californian Wonder Capsicums, Long Yellow Mild Banana Peppers, Serrano Chillies, Caysan Chillies, Manganji Chillies, Hot Long Red Banana Peppers, Californian Red Onions and Burgandy Okra which is still going strong. I experimented with some new varieties of tomatoes and chillies this year and found the Cosmic Purple tomatoes super sweet and very prolific with tall vines and hanging bunches of 8-10 tomatoes each….amazing in salads. Found the Manganji Chillies beautiful and sweet, shallow fried in olive oil with balsamic, garlic and cracked pepper dressing. I’m stuffing the Long Yellow Mild Banana Peppers tonight Italian style with fresh breadcrumbs, anchovies, capers, garlic and Parmesan Cheese…yum. The Okra I will use in a traditional Cypriot vegetarian dish, sautéed in a rich onion fresh tomato sauce with slices eggplant and potatoes….goes well with a freshly baked crusty sourdough. Thanks for the opportunity to share!

.jpg)

Experimenting & Second Chance Successes says: This image is titled ‘second chance tomatoes’! The single tomato plant on the right is a Costoluto Fiorentino that was the ‘runt’ of my late batch of seedlings and the only one that survived a bad case of red spider mite. The tomato plants towards the back are my ‘second chance’ tomato plants, attacked by red spider mite while I was overseas but resurrected for a potential late harvest. I removed the top half of the leaves of the plants that were heavily infested, leaving the tomatoes to ripen. I treated the plants with regular foliar sprays of water ( mites hate it) and dusting of diatomaceous earth. When the last of the top tomatoes ripened, I harvested them and cut the top half of the plant away. This stimulated new growth and once established I removed all of the old leaves. All of the foliage visible in the photo is new and there are also lots of new flowers and tomatoes setting. Fingers crossed my second chance tomatoes might give me an even later crop well into the end of Autumn.

Mrs Cayir (NSW)

.jpg)

Mrs Cayir says: This is the recent Kent pumpkin harvest among my Rosemary and rainlillies. My husband doesnt eat pumpkin but it grows so well that I use it for my confidence boosting haha. The same day we had this harvest a woman on a local facebook page found the courage to ask if anyone had any extra food she might be able to have and we were able to grab a good sized bag of bean, cherry toms and a couple of these pumpkins. We LOVED having these things just surplus and sitting in the garden when we found someone needing them. Looking forward to adding a whole lot more this cool season.

.jpg)

Mrs Cayir says: Our pumpkins being very photogenic amongst the rainlillies

.jpg)

Mrs Cayir says: The care package. Sorry, I forgot the eggs, we had plenty of chicken eggs (last week, this week is moulting season lol) to offer her too.

Jennifer Carnovale (VIC)

.jpg)

Jennifer says: This is the first time I've being successful at growing capsicums and there are lots of them!

Jennifer says: These piles of tomatoes and other veges are one of many harvests since 1st Jan. Cucumbers, tomatoes (Grosse lisse, cocktail variety, big tom), strawberries. I also have silverbeet, spring onions and lettuce in the same garden (pic #3).

.jpg)

Jennifer says: This is my larger vege garden and my pride and joy. I have harvested 57.25kg of tomatoes just in Jan and Feb this year!

Kate Vickery (VIC)

.jpg)

Kate says: Considering this for my bridal bouquet later in the year

Angie Trewhella (VIC)

.jpg)

Angie says: Night harvest of jalapenos for pickling into candied jalapenos!

.jpg)

Angie says: An abundance of chillies to be strung up and dried!

.jpg)

Angie says: Eggplants to be preserved in herbs and oil!

MJ (NSW)

.jpg)

MJ says: My first harvest, experimenting to see what grows best.NSW South Coast

.jpg)

MJ says: cucumbers and basil pesto for dinner tonight

.jpg)

MJ says: Keith the Kookaburra keeping an eye on things

Cin in the ‘dale (NSW)

.jpg)

Cin in the ‘dale says: When you notice the difference between homegrown and supermarket produce! Garden proud.

.jpg)

Cin in the ‘dale says: When you move from a big city to the regional nsw, live in a cool climate but you nail a few veg and also own chickens for the first time!

.jpg)

Cin in the ‘dale says: When you have never grown garlic before and there is that moment when you harvest a few big healthy beauties and do an awkward dance! Also added bonus of keeping the vamps away when drying out for consumption. Garden proud.

Max Giucastro (VIC)

.jpg)

Max says: This is this year's bumper crop of white onions that I planted in 2024 from seeds I bought from the seed collection. I have enough onions to get me through to the next planting season.

.jpg)

Max says: Spring onions also were plentyful from my plantings. I don't believe in using chemical sprays in my garden. If I have pests that are out of control, I will only use home made vegetable oil sprays. Most of the advice I get for my gardening is actually on the seed collection website site, it is full of articles on how to's.

.jpg)

Max says: Here are my kangaroo island purple garĺics which I also sourced from the seed collection. For many years I tried time, after time, to plant supermarket garlics that had sprouted in my pantry so I figured they would grow.

However every time I was disappointed with small or rotten useless garlics.

This time in 2024 when garlic planting season arrived, I thought I should try proper seed garlic instead of supermarket garlic. The proof well as you can see is in the photo of this year's bumper crop of my backyard organicly grown garlics.

Thanks to the seed collection information on the website, and the garlics that I purchased from them I will do the same this March.

Megan Macalpine (VIC)

.jpg)

Megan says: We were delighted with this recent winning entry in the Berwick Show. The French pumpkin was the highlight, together with South African gem squash, a variety of capsicums, brinjal and potatoes

.jpg)

Megan says: The display of fresh herbs was also a winner. Six different kinds, namely Sorrel, Mint, Lemon Verbena, Bay Leaves, Oregano and Curry Plant. We enjoy being able to collect a large variety of herbs from our garden for our own use. They perfume the garden and add taste and texture to food. There are so many good things about a veggie garden or a herb patch!

.jpg)

Megan says: Whilst the Jerusalem Artichokes (bought from you!) didn’t win a prize, we were so happy with the success of growing them for the first time.

Tien (VIC)

.jpg)

Tien says: There is nothing that brightens the day, and WFH desk, than a freshly cut bunch of flowers! My harvest includes sedums, lemon myrtle (smells amazing!), roses, zinnias (seeds from the Seed Collection) and dahlias (Cafe Au Lait, Salmon Joy, pink cactus Superior, white pom pom Little Angel and Atlantic Jewels). I have a small garden in Melbourne suburbia. Being able to grow flowers among the vegetables, herbs and fruit trees is immensely rewarding. Being able to share it with other like minded green thumbs makes it even better! Enjoy!

Turrumbi hobby farm (NSW)

.jpg)

Turrumbi hobby farm says: Blue Butterfly pea flowers, pineapple, guava, grapes, passion fruits, banana, Tamarillo, kiwis, pepino, quail eggs.

.jpg)

Turrumbi hobby farm says: Autumn harvest Butterfly blue pea flowers, Wampee fruit, cucumbers, dragon fruit, pineapple, passion fruit, Zucchini, grapes.

Grace (NSW)

.jpg)

Grace says: I planted these Autumn Bliss raspberry canes in July 2024, 10 days after I had given birth to our daughter Sophie and have named them “Sophieberries”. 7 months on baby Sophie has finally been able to enjoy the first harvest of these special plants!

.jpg)

Grace says: This small and humble harvest is a reminder that each season will end and make way for a new season. After giving birth to our beautiful baby girl in July 2024 I was really struggling with post natal anxiety and rarely left the house. But spending 5 minutes then 10 minutes and now hours in the garden with my little one has been the saving grace I needed. I cannot imagine a world without gardening!

.jpg)

Grace says: After months of expectation, my 3 glutinous corn plants yielded 1.5 cobs of corn. However these are a variety uncommon in Australia and remind my mum of her home in South Korea. Small as they may be, the smile on my mum’s face made it all worth it.

Nadia (NSW)

.jpg)

Nadia says: A marvellous season for the marketmore cucumber in the wicking bed. 16 plants produced close to 200 cucumbers. At one point I was picking 8-10 every 3 days. I made heaps of excellent bread and butter pickles with it. It was the perfect variety!

I also had about 10kg of delicious Tommy toe, tigerella and polish tomatoes. Excellent for eating and the polish are great for tomato chutney.

.jpg)

Nadia says: My marketmore cucumber pickles were perfect. And polish tomatoes suit chutney making!

.jpg)

Nadia says: My wicking beds in action. It became a beautiful lush forrest of vegies!

Linda (QLD)

.jpg)

Linda says: I just love growing Pumpkins, they are so easy! So many different ones ~ Jap, Aussie Blue and there was even a little butternut which was eaten quickly! Delicious!

.jpg)

Linda says: Our baby Butternut and another Jap! Off to be roasted!

.jpg)

Linda says: My first attempt at growing Capsicums, cute little fella!

Knomor Park (VIC)

.jpg)

Knomor Park says: A truck load of produce and pretty flowers!

.jpg)

Knomor Park says: The truckload has made its journey inbound to the kitchen! Ruby red chard, eggplant, capsicum, a variety of tomatoes, rocket, basil, barlotti beans, zucchini, carrots, cucumber!

.jpg)

Knomor Park says: What doesn't get eaten immediately gets preserved for a later day! Cannot wait to enjoy crab apple jelly on toast, or on a cracker with a slice of Camembert. Bread and butter pickles will be served with steak in winter. Sandwiches with lashings of zucchini pickles, ham and cheese will be enjoyed any day in school lunchboxes!

Living-mudflower (NSW)

.jpg)

Living-mudflower says: Nothing compares to the tastes of fresh sweet corn on the cob dripping with butter and salt. This variety tastes sweet, it is higher in antioxidants than yellow corn, and holds a lot of sentimental value. I bred this purple and white sweet corn when my daughter was born because I thought a little girl would be more likely to eat her vegetables if they were pretty. I also wanted a family heirloom to pass on. Creating this unique sweet corn has meant my kids have grown up eating vegetables that are as beautiful and delicious as they are healthy.

.jpg)

Living-mudflower says: I like parsley, it is so simple to grow and highly nutritious, unfortunately most varieties are too small to be very useful. I put some effort into sourcing as many different varieties I could, and crossing them, and culling, and crossing again, and developed this. The result is a giant parsley that makes other 'giant' varieties look small. We use this as a leaf vegetable, use the petioles like celery, and the roots are delicious when roasted. It is just as easy to grow this giant variety as it is to grow small unimproved varieties. The benefit of this is it is something we created ourselves.

.jpg)

Living-mudflower says: We have a few apple trees, these are from Pink Lady. Placing stencils on red apples while they develop means the area under the stencil does not turn red, and words or pictures can be stenciled onto them. This takes time and dedication, but is worth the effort. My kids love eating apples that have been stenciled like this, and they are a big hit at pre-school where they help to encourage other kids to be excited about eating ad growing fruit.

QueenPenelopespatch (VIC)

.jpg)

QueenPenelopespatch says: Autumn garden grocery harvest gives you a bit of everything. We have cucumbers, tomatoes, zucchini, eggplants, beans, chilies, capsicum & springonions. The fun in this mystery harvest is now planning the cooking for the week from this lot.

.jpg)

QueenPenelopespatch says: I love chillies and am a chilli nerd. We grow chillies to preserve & use during the year. We freeze these but seperate them into three categories, mild or omlette chillies, everyday chillies (spicier ones) and Proceed with caution (the ones that will set you on fire) chillies.

Varieties include Turkish snakes, shishito, bulgarian carrot, long cayanne, black muleto, purple cayenne, serrano, caysen, Jalepeno etc. We have more chilli varieties in production too.

.jpg)

QueenPenelopespatch says: The beauty of this harvest is that everything was pollinated by the bees. The Honey melon was the sweetest I have tasted. We have a Cinderella pumpkin, long melon, zucchini, peppers & chilli. Added some Dahlias for the coffee table.

Peta Rogers (TAS)

.jpg)

Peta Rogers says: The pure taste of summer, sunshine trapped in tasty tomatoes! Down here in Tassie it’s a talking point, “when do you plant your tomatoes and when did you get your first one to eat?” Such fierce competition! My love heart of tomatoes are Black Icicle, Jaune Flamme, Tommy Toe, Yellow Pear, Honeybee and Black Cherry.

.jpg)

Peta Rogers says: Supermodel of the flower world. My Giant Russian Sunflowers grew to 2.9 metres tall this year and survived the strong winds. So proud!

.jpg)

Peta Rogers says: One of my Giant Russian Sunflowers. Guaranteed to put a smile on anyone’s face

Daisy Attenborough (TAS)

.jpg)

Daisy says: An abundance of produce from the garden! Spray-free (thanks to the wrens, frogs, spiders and skinks for picking off most of the bad bugs this year), all the plants are heirloom/organic, giving us incredibly tasty, nutrient-dense produce. There's a vaseful of edibles, including dahlia, salvia and fuchsia flowers, traditional herbs, and Tas natives such as Warrigal Greens, kunzea, and river mint. We experimented with fermented dill pickles, made sauerkraut from late red cabbage, cooked Japanese quick pickled cucumbers, created capers from nasturtium seeds, and made calendula salve and lavender body balm from the flowers in the garden. The basket of fruit and vegetables were lip-smackingly delicious!

.jpg)