It's fair to say that beans aren't often considered the most glamorous inhabitants of a garden. Wigwams and trellises covered in the climbing vines are a familiar sight in veggie patches across the world, but the plants are more often grown for their easy productivity than their looks.

One exception is the scarlet runner bean, or English runner, which adds spectacular looks to the usual bountiful yield. Here's what you need to know to grow the plant from seed to harvest.

Runner Bean History

Botanically, the scarlet runner bean is known as Phaseolus coccineus, and is a close relative of the common bean Phaseolus vulgaris.

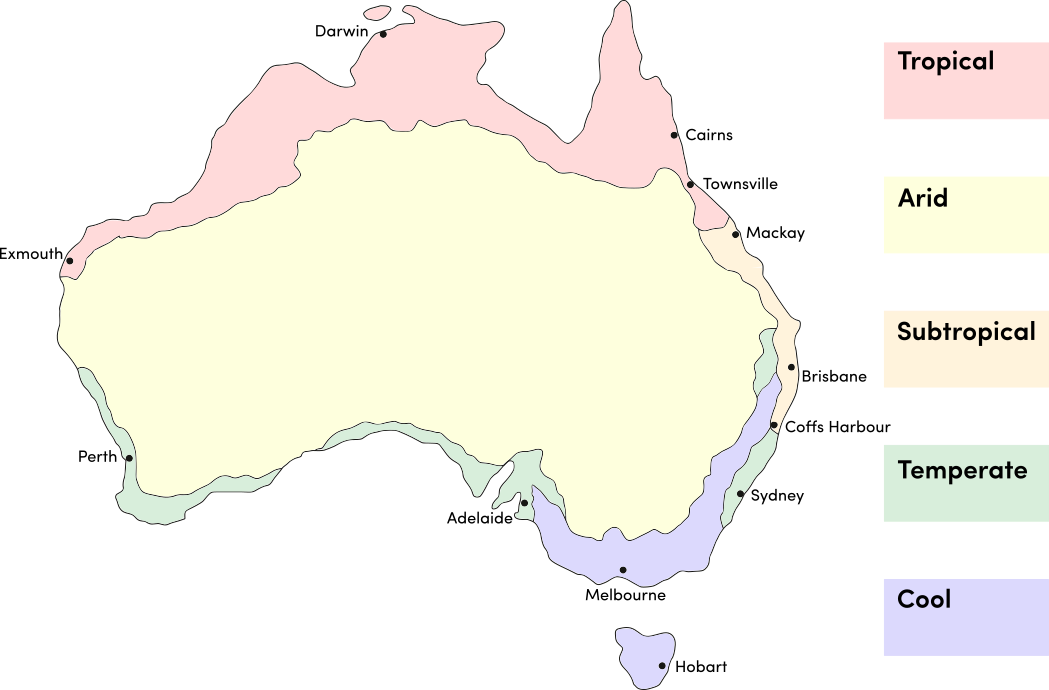

Originating in mountainous South America, it's a warmth-loving bean that needs temperatures of 20C or more to reliably germinate and thrive. It's also known as the seven year bean thanks to the plant's ability to return year after year, growing a tuberous root that'll provide fresh growth each spring so long as there's no winter frost.

Scarlet Runner Beans in the Garden

Scarlet runner beans are hugely vigorous growers, and in native conditions can potentially reach 6m in a season. Of course, your garden and climate is unlikely to produce such monsters, and in any case upward growth can be controlled by pinching out the growing tips once the vines reach a height you're happy with.

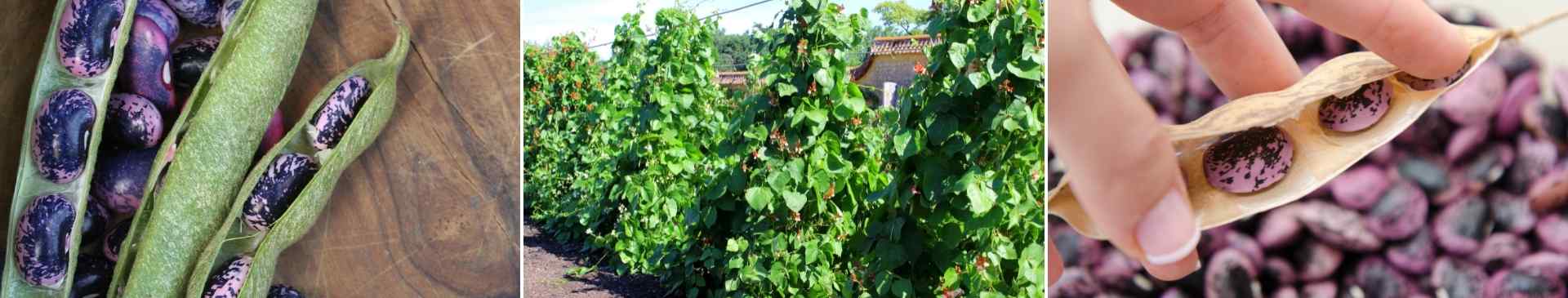

The plant grows with a single stem which spirals up and around support, bearing large, green, deeply veined leaves. A couple of months after germination, the plant will develop clusters of dramatic scarlet flowers.

Once pollinated - see below - each flower in the cluster will go on to produce a pod, which at maturity will be flat, fibrous, 1-2cm wide, and up to 20cm long.

When the pods are young, the seeds inside will be a pale pink which darkens over time to a deep violet, eventually turning to a crimson-speckled black. The final seeds will be around 2-3cm long, with between six and eight in an average pod.

Runner Beans Nutritionally

Like their common bean cousins, runner beans are rich in vitamins C and K, and also contain useful amounts of folate and manganese. They're high in fibre, good for aiding digestion, and low in both carbs and calories, making them a helpful part of a weight control diet.

Runner Beans in the Kitchen

Runner beans are a little tougher and more fibrous than common beans, which makes them less widely favoured in classical kitchens. However, their earthy flavour has its own attractions, and the rest of the plant offers plenty of culinary versatility.

- The scarlet flowers are sometimes the main reason the plant is grown, earning it a place in purely ornamental gardens. However, don't overlook the culinary possibilities of the blooms, which have a mildly bean-like flavour and make an interesting addition to salads.

- Young beans can be treated as sugar snaps and are tender and sweet enough to be munched raw, pods and all. As the pods get larger, they become increasingly stringy and fibrous, and boiling or steaming is necessary for tenderness.

- Importantly, once the beans inside the pods start to darken from their initial pink, cooking becomes essential to neutralise the small traces of potentially toxic lectins they contain. But this is a case of being better safe than sorry: it takes a fairly monotonous diet of beans over long periods to ingest enough of the lectin to be dangerous.

- Leave the pods to reach full maturity, and you can harvest the beans inside for drying, and later use them in stews, purees, and so on.

- And finally, if you don't want to let the seven-year bean regrow next year, the tuber can be dug up and used as a starchy root vegetable.

Growing Scarlet Runners

Most beans prefer a mild and sunny location, but warmth is especially important for this South American native. Germination is unreliable in soil temperatures below 20C, and the plants grow most vigorously in warmer conditions.

They also like well-drained soil that's rich in organic material, so dig plenty of rotted compost or manure into the patch before sowing.

Choose your spot wisely, ideally keeping these climbers out of strong winds, and sow the seeds direct in late spring or early summer when all risk of frost is past. The seeds should be sown 2-3cm deep, spaced 12-15cm apart, and in rows a metre apart.

This tall and gangling plant needs sturdy support, so provide a trellis, a cane wigwam, or an a-frame from the beginning: the vines will naturally seek out and twine around the support as they grow.

Runner bean vines prefer moist but not waterlogged soil, so water regularly but fairly lightly, keeping splashing to a minimum to prevent fungal problems developing. Adding a mulch to the soil can help it retain moisture, reducing the need for continuous watering.

If the soil is rich with organic matter, beans should not need any heavy feeding as they grow. If you do need to use a fertiliser, avoid nitrogen-rich formulations as they will boost foliage at the expense of flowers and pods.

Pollination Issues

One common difficulty in growing runner beans is that the plant produces plenty of flowers but few resulting pods. There are two possible reasons for this.

First, although runner beans love warmth, extreme heat will discourage pod setting. In particularly hot or sunny weather, misting the flowers with water can encourage more of the flowers to set into pods, giving larger yields.

But perhaps more importantly, unlike other beans runners don't self-pollinate, and are highly dependent on bees, moths, and other pollinators to do the job. If your garden lacks these helpers, try planting a few sweet peas or other attractive plants to increase the population.

But if all else fails, you can take on the pollination duties yourself. Using a fine paint brush, gently dab the pollen-containing stalks within the flower, known as the anthers, to transfer pollen onto the bristles. Next, touch a little of the pollen to the inside base of other flowers, which should be enough to encourage a set.

A less delicate method is to snip off a single large flower, and gently press it face-to-face into the other flowers on the plant, which is quicker if a little less scientific.

Harvesting Scarlet Runner Beans

As with all beans, regular picking encourages fresh flowering and extends the season. Picking the pods young provides the sweetness and crunch the runner is most prized for, and the harvest should be used as soon as possible to preserve flavour.

Larger pods can be picked and cooked within a day or two or blanched immediately for storage in the freezer. Pods which have become large and fibrous are perhaps best left to develop full-size beans for drying, although this will put an end to further pod production.

Common Scarlet Runner Bean Problems

Given the right conditions, runner beans are reliably productive and take little looking after. However, at the seedling stage they're vulnerable to slugs, snails, and small feeding mammals such as rabbits, although once the stalks toughen up these pests are less of an threat.

Aphids can cause problems, so inspect the plants regularly and deal with any infestation as soon as you see it.

One common problem is powdery mildew, which forms a dusty grey layer over the leaves. This is usually caused by poor airflow and high humidity, so take care over spacing, and water carefully to keep splashing to a minimum. Affected leaves can be removed and burnt to help keep the spread under control.

And lastly, there are a few viral and fungal disease which can affect bean vines. If you see discoloured spots on the leaves which develop into holes, then an infection is likely, and the safest option is to dig up the whole plant and dispose of it away from your compost heap.

But these minor problems aside, growing just a few runner bean plants in your patch will usually provide a generous harvest using very little space or gardening effort.

_850.jpg)