The entire kingdom of plant life is founded on seeds, which is perhaps surprising for things that look so small and lifeless. But while seeds in a packet don't grow, feed, reproduce or show any other signs of life, they're far from dead. Instead, they're in a state of deep dormancy, ready to spring into action when the right conditions are met.

To understand how this happens, it's helpful to know what a seed contains, and how its contents provide everything that's needed to create a new plant.

What's Inside a Seed?

Even the smallest, most boring-looking seed can grow into a full adult plant, thanks to the various parts that make up each one.

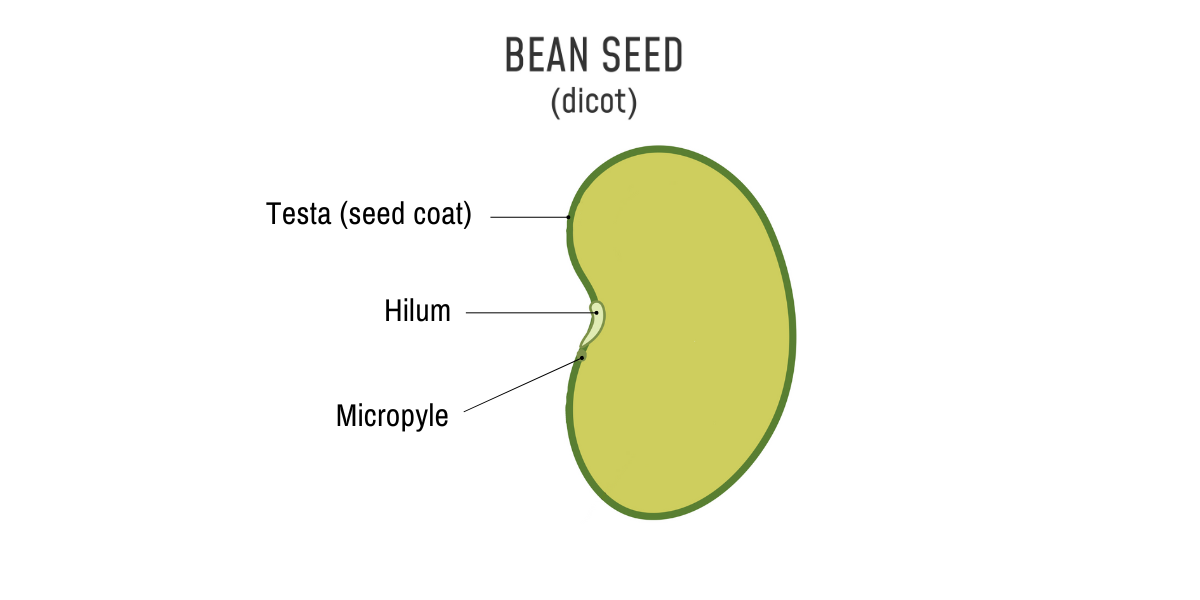

The most obvious part of a seed, the tough outer casing, is known botanically as the testa, though it’s often called the ‘seed coat’ in common gardening lingo. The testa protects the seed's contents until the time is right for germination. It keeps most of the moisture out to stop the inside rotting, as well as protecting the delicate internal parts from physical damage.

Other parts that you might see on larger seeds include the hilum, which is the scar left over from where the seed was attached to its parent plant. Think of the hilum as a seed's belly button! There's also the micropyle, which is a small pore in the coat that lets a minute amount of moisture through to keep the seed ticking over until it sprouts.

Inside each seed, there are four main parts that come together to produce a seedling. And while they might have fairly technical-sounding names, they're pretty straightforward in what they do. Each seed contains:

- The radicle, or the beginnings of the first root that appears during germination.

- The epicotyl and hypocotyl which together form the seedling's first stem that pokes through the soil.

- The cotyledon which contains a small food store for the seedling along with the starting points for its first pair of leaves.

The seeds of grasses, including corn, have relatively small cotyledons but also include an energy store called the endosperm. The endosperm provides energy for the early growth of the plant.

.png)

What Makes a Seed Germinate?

Seeds need the right conditions to leave their dormant state and sprout into seedlings. While the exact details are different from species to species, all seeds need:

- Enough water passing through the outer coat to spark off germination, but not too much to 'drown' it or make it rot.

- The right temperature to trigger germination. For some seeds the required temperature mimics spring conditions in the plant's natural climate, while for others there's a broader temperature range that's suitable for germination year-round.

- The right amount of light for that particular seed, with some preferring a little daylight, others almost full darkness. In most cases the amount should be similar to the typical daylight levels at the time of year the seed would germinate in nature.

- Seeds need a little oxygen to break down and release the energy stores that power growth, so they shouldn't be fully submerged in water.

- Lastly, although many seeds can be germinated without soil, for example by spreading them on a wet paper towel, sowing seeds into good soil helps to provide consistent conditions for both sprouting and the early stages of seedling growth.

What If I'm Having Germination Problems?

Unreliable germination is one of the most common problems for gardeners who grow plants from seed. If the conditions seem to be right but you're still having trouble getting the seeds to sprout, there are a few things to check.

First, although seeds are mostly dormant, they're not totally in a state of suspended animation. There's a tiny amount of 'breathing' and energy use going on, and the longer the seeds stay dormant, the more of their resources they use up. Eventually, the seeds will be too old and dried out to germinate successfully, so check a seed's age and how it has been stored if nothing seems to be happening.

The next most common problem is that not enough water is reaching the seed's insides. Generally speaking, conditions that are consistently moist but not wet are perfect. In hot weather, covering the seed tray with plastic wrap or similar will prevent the soil from drying out between daily watering.

For some hard seeds, soaking them before sowing can soften up the shell to let more moisture through and speed up germination. For especially large and tough seeds, lightly nicking or scratching the seed coat can help water find its way in. While some ‘pre-treatments’ are optional, they will be listed on seed packets if they’re needed for germination.

Lastly, some seeds need special circumstances to germinate, especially those from native species. Some might only sprout after a bushfire passes by, and so will need this to be simulated, for example by adding smoke extracts to the soil when sowing. Others might only germinate in nature after passing through an animal's digestive system, so you might need to roughen up the shell before they'll sprout (or even sow the seed into manure!). In these more unusual cases, the seed packet should give the right instructions to follow.

In general, the humble-looking seed will happily sprout and grow into a full plant if it's given the right conditions. Getting to know your seeds and their needs will add extra success and satisfaction to your gardening.